I used to be an adventurer and paint myself entirely red every Saturday, because you know, like, art, but now I am grown up and I am just hoping to avoid death instead of careening mercilessly towards it.

Paint is, for the most part, extremely toxic. Paints made for children are thrilled to claim non-toxic status in bright yellow banners all over the bottles. You get the feeling you could eat paint for kids and not suffer, and you probably could.

Each tube carries a serious warning label.

Meanwhile, fine art paints for adults making adult paintings will probably kill you. Paint has always been bad and we haven’t solved the paint toxicity problem yet - if painters of the last century weren’t taken out by murder or heartbreak, chances are good they would get mentally eroded by just being around cadmium or lead too often.

Warning labels in 2018 on paint tubes beg: Don’t put this down a sink. To communicate this point even further, labels on paint thinner, even the kind you get from Michaels, display illustrations of a belly-up fish emerging from a black river. Sewage systems can handle soap, shampoo, laundry dirt water, toilet water, but not this wicked brew.

The most charitable way to dispose of unused paint and turpentine is to seal it in a tin and bury it, but ideally you could blast it into space, where it would never touch earth again.

Ironically enough, the earliest forms of turpentine originally dripped down from trees. A trustafarian in a yoga pose saying ‘only eat from the earth, mannn’ comes to mind, where the earth produces the most toxic poisons of all, and humankind just happens to be very good at finding them. Turpentine today is a chemical soup of god knows what, but it’s still just as harmful as ye olde Tree Turpentine.

So what’s a painter to do? We want to make beautiful things, but all of it is so deadly. Here are a couple tools I’ve used over time to die less quickly while painting.

Gloves and Liquid Gloves

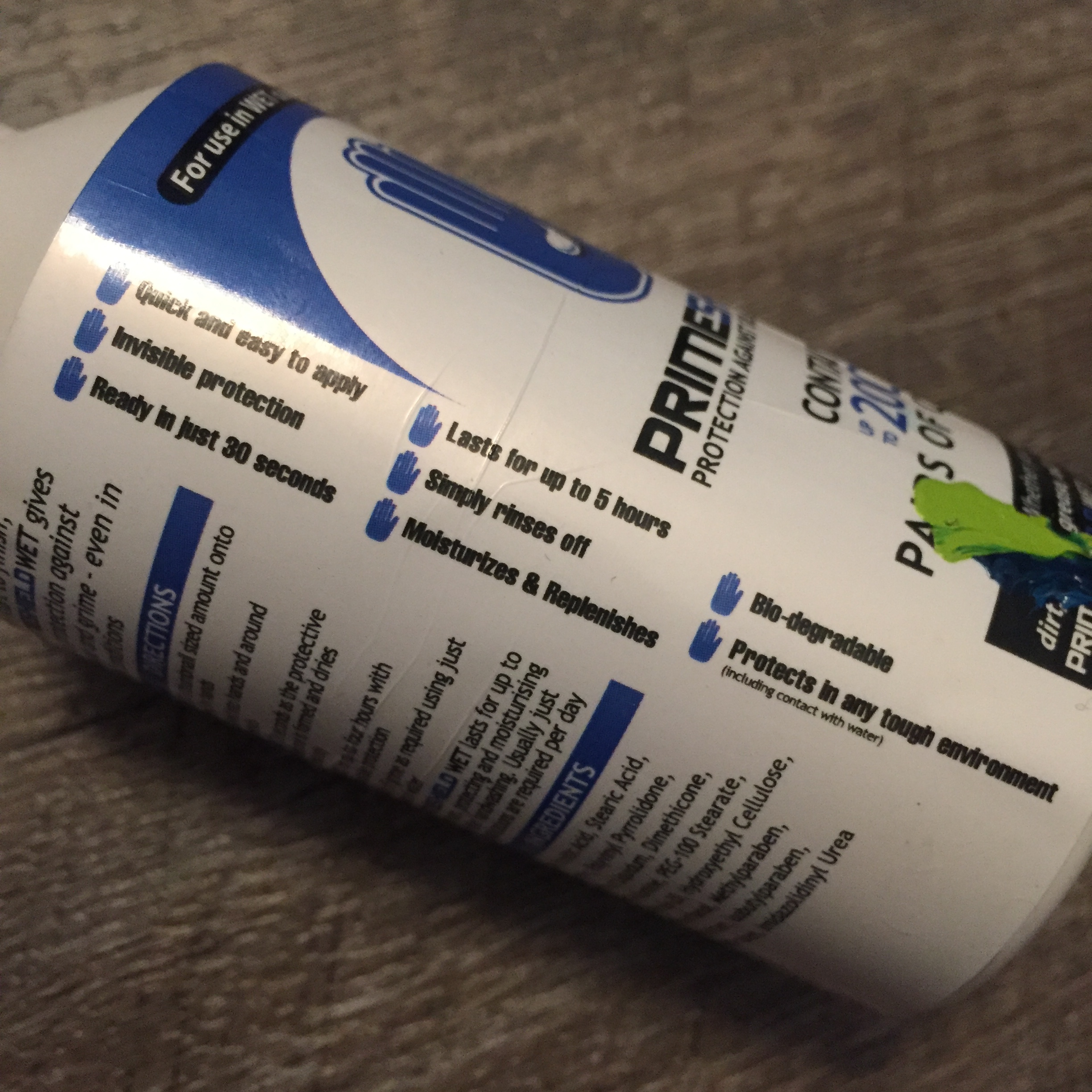

I gave this Primesheild Liquid Gloves product a try. I still get paint all over my hands, but I believe that the liquid gloves are blocking the paint from entering my bloodstream.

Primeshield gloves are great, I can paint all day and don’t have to worry too much about cadmium sinking into my veins. But, I believe in the protective ability of latex gloves a bit more, because the paint is definitely on the gloves and not sinking into my hands.

The problem is that it’s hard to feel brushes through gloves (insert sex joke here, thanks, I’m here all night). The Feeling Problem is the entire reason liquid gloves were invented - for people working with sophisticated machinery, or for nail salon technicians who are painting delicate flowers on fingernails, gloves make careful processes feel like playing a piano with mittens. At best, gloves throw a clinical light onto the process of painting.

At the end of the day, you have to choose liquid gloves, latex, or no gloves. No gloves seems to win, as hand protection is one piece of Art Life that goes missing from most popular tutorials. Bob Ross isn’t out there wearing gloves or a mask, and most hobbyists and full-time painters aren’t, either.

That said one of the best things about Bob Ross is that he does a great job of keeping his brushes clean. He also has a huge amount of space, which I hope is ventilated, it’s kinda hard to tell. ;)

Plein Air Painting

Ironically one of the best ways to avoid inhaling toxic paint is to paint outside. Turpentine in the air can be dangerous at anywhere above 100 PPM, but this problem goes away if you are surrounded by more air than walls. This sounds too simple to be useful advice, but painting outside isn’t done often for a reason.

Painting outside seems romantic and whimsical until you’ve painted a perfect happy tree and a giant moth flies right into it. The moth’s day is ruined and so is your painting. En plein air is really the most demanding form of painting there is, requiring in-the-moment creativity, physical strength to get to cool locations, and mental resolve to deal with wind, dirt, bugs, and people who want to say hi to you and learn about art. The chemical problem IS solved in plein air, however, as long as the artist isn’t spilling too much paint on the beach.

Plein air painting: Looks romantic, actually hardcore af

It’s an environmental concern to never spill paint or turpentine while plein air painting, or the river becomes like the one in the warning label.

Paint thinning and cleaning brushes:

Ironically along with being able to make your face bright and shiny, Shu Uemura facial cleansing oil takes good care of paint-splotched hands and paintbrushes. It probably sounds like a sacrilege to use this product on anything but your face, but, at it's core, it's oil, and oil cleans oil. Instead of stripping the moisture out of paintbrush bristles, it conditions the bristles, making them smoother. I like this Anti-oxi version, even though I know it won't really save me from all the toxins in my life, and have only bought two bottles in the past two years. They last quite a while.

Shu Uemura is a part of my art studio

I also use makeup wipes to clean brushes and clean my hands. If they’re gentle enough to put on your face several times a day, surely they are gentle enough to use in the studio. There are also artist-branded studio wipes out there, which are good. Either works.

The Lengths

Why is art history so dramatic? All of the drama of art history boils down to this: Look at the lengths that people will go through for an image.

There are discoverers and historians who go through The Lengths: People will walk through deserts for months to find a painted hippo figurine.

How far would you go for this hippo?

Artists themselves go through The Lengths. Think of the painters painting the ceilings at Versailles, twisting their spines to paint the toe of an angel. Think of Chinese artisans making clay statues under pain of death, or Michaelangelo putting off his paid commissions to work on his own stuff.

There are people out there who steal art for money, and some people who steal art because it looks cool, because they just want to have the art. All of this is the drama of art, The Lengths that people will endure to just … do what? Have an image.

The FBI’s top Ten Art Crimes (https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/art-theft)

When making art, there’s no guarantee that the image will last, or that anyone will like it, or that it will make money. Failure of craft as an artist is another form of The Lengths - when it doesn’t turn out as we envisioned, or the paint chips off, or the brush hairs split. But the art still has to be made. The Lengths must be crossed.

The Lengths are why there are still so many toxic chemicals surrounding painters, and why the dead fish under the black tree loses its shock value over time. Unlike ladies of old who used makeup with lead in it, we live in a time where we know cadmium is bad, we know turpentine is bad, but we use it anyways. We know that the graffiti will get painted over next week, but we spray it on anyways. We know that not everyone will like the painting, but we paint it anyways.

It’s not just paint though. Toxic substances are everywhere.

A year ago I went to a Home Depot off of Westheimer in Houston, Texas, to get rolls of window screening - this I later used to create hand-pressed paper. After blending shredded paper and pouring the pulp into a deckle, my great plan for the Home Depot roll of window screening was to use it as a top layer to make the paper smooth, however slightly gridded.

When I unrolled the window screening, an all-too-familiar death warning label fell out of the bundle:

"This product has been treated with a chemical known to cause cancer in the state of California."

I imagined the Home Depot-loyal families of the world going in and out of their front doors each day, drifting past this same mass-produced window screening. None of these imaginary-but-real people were necessarily artists, but they'd still be touching and breathing the same screen that I was using to make art.

In this moment it was plain to see toxic substances as unavoidable for almost anyone living in the modern world. Like the tree that bleeds turpentine, toxins emerge from the most innocuous, omnipresent things of our lives. This year, even coffee was declared to cause cancer in the state of California.

I looked at the warning label on the window screening and took a deep breath. When it comes down to it, art is incredibly dangerous, but so is being alive. We might as well make art.

Related blogs: