When Edvard Munch painted The Scream, also translated well as ‘The Cry’ or ‘The Shriek’ he was chasing either a vesuvian nightmare, or possibly painting the sickness and death he saw all around him. That is the base interpretation, at least.

The Scream was a rare moment where Munch took his subject out of an enclosed space and threw it into the wind.

Munch's other glimpses into human suffering often occur in interiors, in cramped spaces or dark areas. The lithograph ‘Madonna,’ while not overtly about imprisonment or suffering, was framed with a chain of sperm and a baby-like cartoon curled into the corners of the frame. Some conjecture that the fetal character is Munch himself, a furled creature overwhelmed by the sexiness of the young woman. Life is hard if you are a Munchian subject!

For Munch’s work with figures and human beings, it was all about entrapment,

enclosure ....

and limited space.

Except in The Scream, where everything is occurring in the open air.

Being so open and ambiguous, The Scream is unlike any Munch landscape and unlike any Munch figure. It truly makes no sense. Munch could paint believable faces; he had a good sense of how the bones of a face plane out into colors. He knew how shadows and light fell across a jawline. He knew that eyes were globes lodged in sockets. Given what he knew in other paintings, the face in The Scream is ridiculously unstructured. It isn’t even a skull. It’s ... something else. Some scholars follow the vesuvian theory - positing that the figure is either meant to look like a Pompeii mummy, or that Munch subliminally painted it so. Others say the figure is like the sperm doll in the Madonna lithograph. At universities worldwide, arguments with youtube-comment levels of ire take place over whether the figure is pre or post-life.

While this argument matters to a degree, what matters more is the ineffable quality of the face. It is so indeterminate, it could be anyone. It could be you, me, or someone we passed at the supermarket this morning. This indefinition is why so many derivatives of The Scream are made. We can all imagine ourselves, Lisa Simpson, Batman, or our least favorite politician as the screaming person. It's a painting that can be mapped onto anyone.

The pile of derivative works of The Scream wouldn't have happened if the screaming person had looked like the girl in Puberte or the woman in Madonna. Nobody could easily swap in for either.

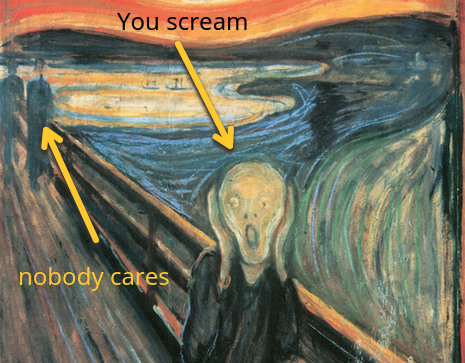

But this assessment, that anyone can be the screamer, is also flawed. The most logical, point-blank understanding of the painting is that we, the viewer, are the horror. We are not the screaming person, we are the thing that is being screamed at.

And absolutely, what makes The Scream most relevant and terrifying is not the person screaming, but the disinterested, ambiguous figures stationed several meters behind. Who knows what the distant figures feel, if they feel anything at all. The scary thing about The Scream isn’t the screaming person, it is that nobody hears. Nobody is rushing to assist. The inability to scry the intentions of the pedestrians casts an eerie feeling onto the painting, with shades of an isolated modernity that Munch understood and many still do: the louder you scream, the less they care.

In other renditions, sketches, and predecessors of what we call The Scream, all of the figures are the same. A single pensive person, or a screaming person occupies the foreground, while disinterested parties stand further on.

The Scream became a resonant image in our centuries, as it captures every person who suffers alone, who nobody cares about. Someone screams, they are not alone in a forest, but still the scream does not make a sound.