On a long enough timescale, all art has to stand alone. Eventually, there are no explanatory placards, no audio guide, no artist’s statement. There’s just a painting on the wall and nobody knows where it came from, who made it, or what it means. There are pictoglyphs in Utah and nobody knows who made them - they’re 3000 years old.

So why read the letters of an artist if the works are iconic enough to stand alone? We already know Vincent van Gogh is great. Do his paintings need words to back them up?

Why dive deeper into eternity?

In the case of Vincent van Gogh, the letters tell us that he was not just the best painter, but one of the best people to ever be on the planet.

Most people know about Vincent’s mysterious end, but few could summon thoughts about his more optimistic early years. In his younger years he seems to be full of hope, so much that he is ready to give life advice to his younger brother Theo. In his letters he talks about polishing his boots and encourages his younger brother to eat well, especially a lot of bread:

He polishes his boots, he eats bread, he keeps up with his brother and anticipates future letters. He writes to send letters, and writes to get letters back.

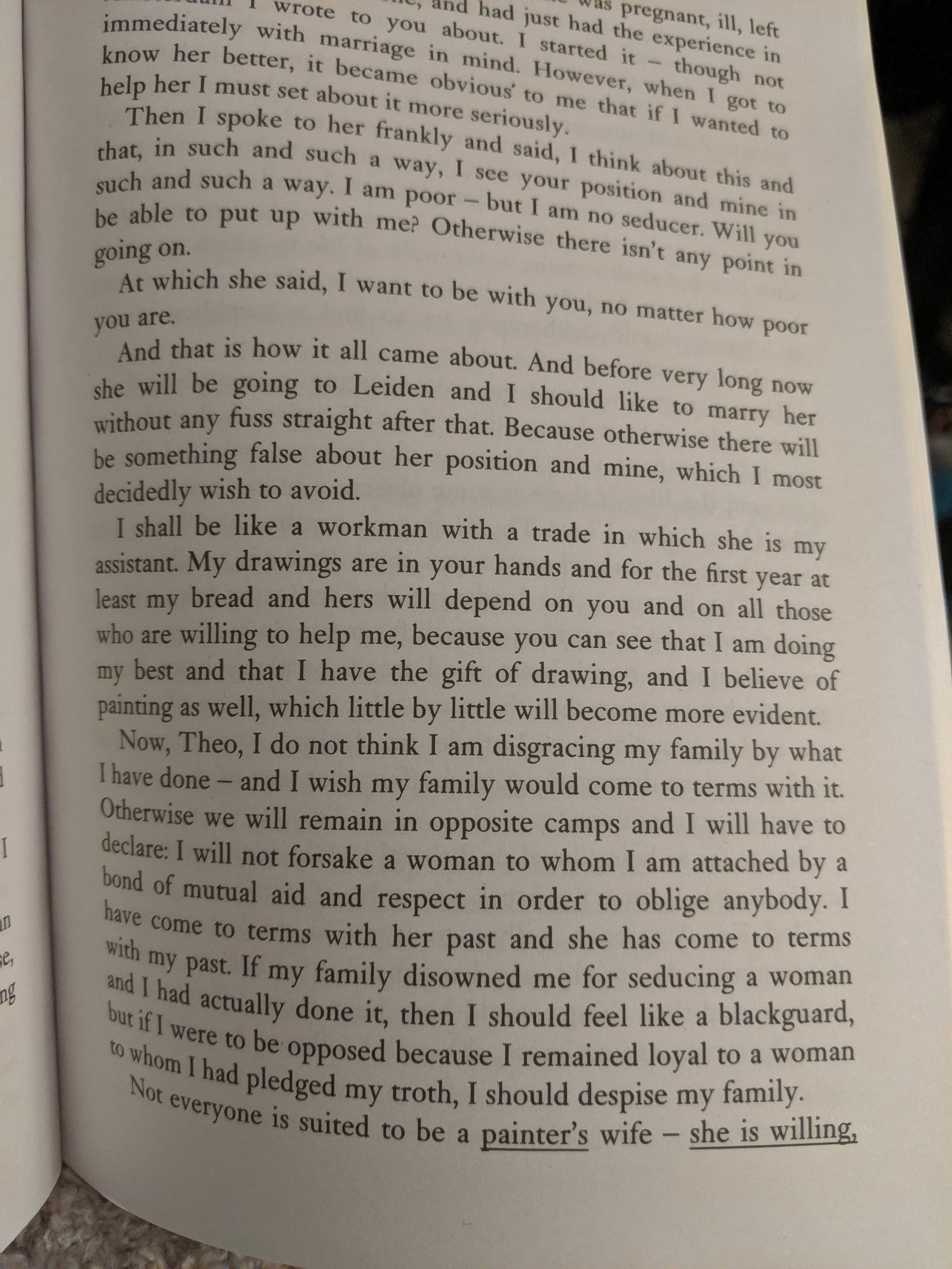

The letters arc like a novel, where Vincent starts out relatively orderly, optimistic, and powerful (eat bread!) and he ends up in a place where he has to ruthlessly defend his choices against his entire family, like in this passage where he falls in love with a single mother, Sien, and brings her into his home.

At the end of the passage above, he is truly like the ideal man in the Spice Girls song “Wannabe,” where Sporty Spice croons: “If you want my future, forget my past.”

We’re almost in a world that won’t judge our Vincents or our Siens. I’m not sure.

Vincent’s world didn’t leave him unjudged. In fact, it barely left him alone. It barely let him do anything, and it’s a miracle he made any work at all.

Vincent dedicates a heartbreaking amount of time to defending himself against his father in letters to Theo. He writes like a man attacked, writing to his only friend. He doesn’t depict himself as a saint, either, he admits he knows he is being stubborn upon several occasions. It’s funny that he writes only to Theo - maybe Theo is the only person in the family who was worth talking to, or, Vincent’s letters to his father were torn up or lost. It’s hard to imagine Vincent writing even MORE than this, but I wouldn’t put it past him.

Vincent seems stubborn at best in his letters-of-self-defense, and not too accusatory of those who antagonize him. And what if he’s right about how terrible his family is? What if his father and mother are stuck in their ways, and the rest of the world is moving on. The rest of the world isn’t aghast at loving a single mom.

When Vincent’s father finally dies, the concerns in the letters transform - Vincent is set free and can finally talk about, well, painting, in his letters instead of defending himself against his father.

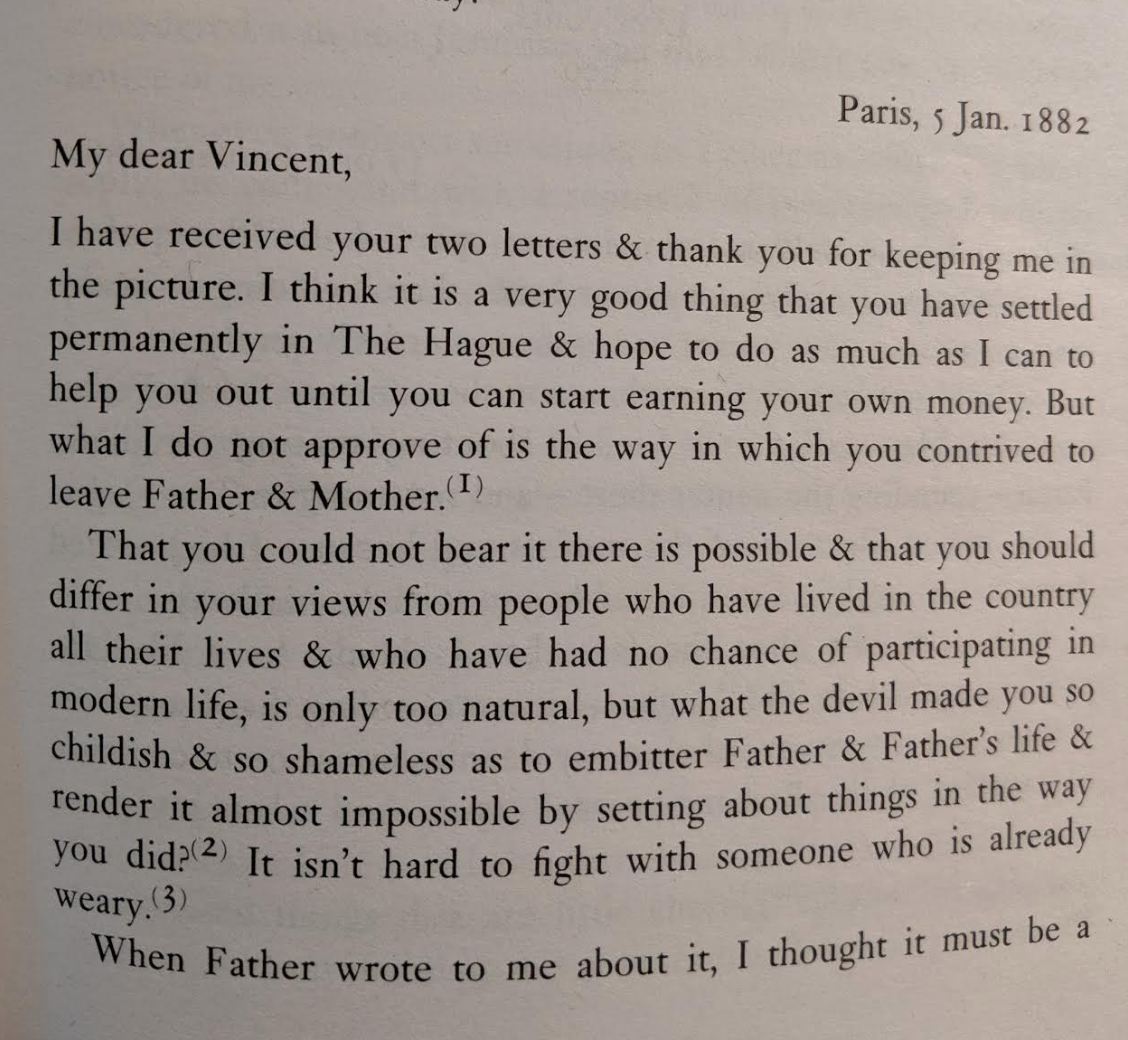

The edition has only one letter from Theo, the Dear Brother, for the first 150 pages. The tone of the letter comes off as “Stop doing what you are doing and calm down, and say sorry to father.” At this point, Theo and Vincent are so upset that they are itemizing each of their argumentative points with numbers (1), (2), ect:

In response to this missive from Theo, Vincent writes back something like 5000 words, each itemizatized response to points (8), (9) ect as long as Theo’s entire letter. It would have been like writing a tweet and getting a novel in response.

Since the entire book is so one-sided - we get dozens of letters from Vincent and only one from Theo, Vincent is easy to sympathize with. You fall under his spell, and it’s a good spell. It’s not like reading the deranged journals of the protagonist in Pale Fire, or reading the diatribes of other mentally-understocked unreliable narrators. Yet, I wondered, what did Vincent do or say that made his colleague Mauve say to him “You are a vicious person?” Whatever it was, Vincent sort of leaves it out of the letters.

It’s more like reading a surprisingly reasonable defense against social crimes that are not nearly as bad as those of Paul Gauguin. Unlike Gauguin, cough, van Gogh never took a 14 year old as a wife - in fact all he wanted was to help a single mom. Van Gogh is like the Samwell Tarly of his time - he's already outcast from his family but falls in love with a single mom and loves her, gives her and her baby a home, and his father berates him for this and for many other shortcomings that Vincent seems to have. Vincent even refers to himself as a ‘nobody’.

If the world had more Sams and Vincents rather than fathers of abandon, imagine where we could be. In fact it’s probably the Sams and Vincents that keep it all together for us, the real fathers who know how terrible life can be for both men and women, and for all people, and who step in where nobody else will. It breaks my heart.

Reading these letters, you start to overly agree with Vincent - the world is actually very dumb, everyone sucks, Vincent is right about everything! But nobody can be that perfect, right? Citing suspicion of perfection, you can find the devil’s advocate on your shoulder wondering over these letters: What if he’s lying?

What if Vincent is casting himself as some sort of saint, where he’s really not?

But then - why would he lie? At best he could embellish, but he’s not interested in looking cool or being a savior. He’s not a land owner or a merchant, he self-identifies as a nobody. The letters are going only to Vincent’s little brother Theo, who isn’t impressed with Vincent at all. If Vincent wanted to preserve and glamorize himself in the eyes of his overbearing family, he would have never written about Sien at all. Instead, he nails himself to the cross.

In my whole life as an artist, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone represented more unfairly in popular culture or more misunderstood by non-artists. Van Gogh’s ear and suicide stand out as some of the most contested facts of art history. Was the ear a chapter of deranged self-harm, or was it Gauguin who chopped off the ear? Was Vincent’s death a suicide or was it a misaligned murder?

I’m not sure if these murder-mystery questions matter as much as we think they do. No matter what hurt van Gogh, we didn’t want it to happen. We didn’t want Vincent to get his ear cut off or for him to cut it off himself. We didn’t want him to kill himself or be murdered. We wanted Vincent to be around for a bit longer.

At one point, Vincent is beaming about how his doctor mistook him for an iron worker, and in other letters he carefully plots out how many years he had left. (Some artists live to 60 or 70!) Yes, carrying an easel all across the landscape will make you pretty buff.

Stress was plowing down on him from all directions - family, finance, occupation. He spent so much time defending his thoughts and choices. Sitting in my bed and staring at the letters, my poodle snoring and a TV show playing in the other room, I thought to myself: “What was the point of all of this fighting with his father ... what was the point of these thousands of words scrawled out across hundreds of pages. What if all of this time could have been spent on painting?”

Ultimately Vincent’s defense of himself and his ideas in his letters did matter for his painting - anyone else would have given up, not just on art, but on everything. His world was just crowded to the brink with antagonism. Vincent’s art didn’t happen because of his painful life, he made art despite it, and it’s simply amazing that it happened at all.

So, with all of his tenacity, why did van Gogh’s life end at such a young age?

I didn’t know what to make of the ending of this novel-of-letters. If we believe Van Gogh shot himself and was not assaulted, it’s as if Theo’s moment of weakness along with Vincent’s worsening epilepsy is enough to send Vincent over the edge. The moment that Theo shows weakness is the moment that Vincent gives in.

But I barely buy the suicide belief because Van Gogh was so interested in staying alive throughout all of his letters. The letters don’t even strike me as unhinged in a slight way, they’re simply very expressive. It wasn’t insane that Vincent could respond to Theo with novel-length itemized lists of arguments, it was just exhaustively comprehensive. Vincent spent his entire life defending his choices, accepting his choices, and believing in his work. Near the end, he even moved to a new asylum in the hope of getting better treatment.

Nobody could have cured Vincent’s epilepsy, but his hope was there. Why work so hard to get better, why be so intensely in love with the world, why defend yourself, and then just throw it all away? I think Vincent didn’t do himself in. It had to be something else.

The Letters are ultimately a mystery novel where there is no answer.

We’re lucky if private writing like Vincent’s letters surface every quarter century. It’s rare to find and even rarer for it to be interesting. Much of Vincent’s letters are brilliantly alive with feelings, and some of it is… Vincent is in the hospital, or he is dreaming about paint going on sale.

So, yes, the letters contain some mundane pieces - it’s not not forsaken romances and family feuds all the way down. Vincent is troubled by the same issues we might run into today - he voices his mistrust of clever lawyers, he gets expensive dental bills.

It’s Vincent’s unrepenting honest love for the world that is a treasure. Seeing Theo’s letter, honesty isn’t present in private letters all the time - letters can be as carefully buttoned up, as repentful, as punishing as life on stage.

Imagine the scholars of the future finding a private Youtube account on a server somewhere - all of it could be a heartbreakingly accurate revelation of our time, or it could be nine-minute reviews of Monster Energy Drinks.

Which could be, yes, it’s own revelation - but not as touching as Vincent scrawling off missives to his brother like “I’m dating a single mom, I don’t care what dad says!”

Where else can we find this honesty? Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations are best thought of as private journals or notes-to-self - Aurelius never meant for the writings to reach the world. Like Meditations, the letters of Vincent van Gogh were meant for the eyes of only one person, yet here we are reading them, translating them, publishing and republishing them, lamenting an untranscended 150 years of dental bills and expensive paint.

Aurelius’s private writings wouldn’t be so odd if other writers in his time weren’t marketing their work as savagely as Don Draper. The Roman poet Ovid was writing highly-sought, wildly popular advice to women on how to look beautiful and sexy in the Ars Amatoria one-hundred years before Aurelius was penning his notes-to-self on how evil never dies.

Even when van Gogh was writing his extremely private, thoughtful letters, Dickens was cranking away at words that would be cast out to thousands and later, millions of people. In our strange little time, we write furiously on Facebook walls and on Twitter, and each scribble has it’s own performative bent - we’re trying to look cool, or be funny, or do… something? Who really knows what we are doing when we share a thought on the internet, but it’s all very on-stage.

Reality exists, privately, and we only get to see it in letters like this. Perhaps the key to truth in art and writing is that we should all create as if nobody will hear us but the person we love most. It might be the only way to be eternal aside from painting.

Related blogs:

Vincent van Gogh at Houston MFAH